The prophet Jeremiah, Angels & Christology, and plumbers for classical education

A Systematic Theology update before summer

“There is none like you, O Lord;

you are great, and your name is great in might.”

-Jeremiah 10:6

June is here at last. And I have been on many adventures since I last wrote, many bringing me further along the road to my Systematic Theology (Baker Academic).

In my Bible reading I have returned to the prophet Jeremiah, and I have been fixated on chapter 10. As Jeremiah compares Yahweh to the idols of the nations, he makes his appeal to creation. While the idols are made by the hands of men, Yahweh is the Creator of men. The gods “who did not make the heavens and the earth shall perish from the earth” but Yahweh “made the earth by his power” and “established the world by his wisdom, and by his understanding stretched out the heavens” (10:11, 12). I am convinced the doctrine of creation is one of scripture’s constant court of appeals, wielded to (a) counter our temptation to domesticate the infinite One, and (b) differentiate between true and false worship. How fascinating: the prophets will appeal to creation once more to give credibility to God’s covenant fidelity.

I do not remember how it happened, but earlier this spring I was lost in the most pleasant way, roaming around in the heavenly realm of angels. After the gloom of winter, I struggled to find my pace with research after spending so much mental energy on prolegomena. Suddenly, I remembered Alan Jacobs’s advice to read for pleasure. So, I figured I had put off my reunion with The Orthodox Faith by John of Damascus long enough. (A new edition has released, published in the popular patristics series by the way.) My instincts proved reliable: on the subject of angels a whole new world awaited me. I have found contemporary treatments of angels to be one-sided, only giving themselves to what angels do. Few theologians tell us what an angel is—modern theology’s prejudice against ontology runs deep still. My systematic will not shy away, but will be so bold to explain the most mysterious of questions: Is an angel made in the likeness of God? Do unfallen angels experience the beatific vision? Do angels know divine ideas in a way no man can? How does an angel know this creaturely world when an angel is not composed of form and matter? Why is a fallen angel irreconcilable while Adam’s fall was remedied by reconciliation? Et cetera.

At the end of the spring semester my wife, Elizabeth, surprised me. With The Reformation as Renewal (Zondervan Academic) off to the printer, she knew I was eager to made headway on my systematic this summer. So, she sent me away on a three-day research leave to Kansas University. KU proved the ideal setting with their many libraries, each library housing different books. This study leave gave me the chance to turn the corner from angels to Christology. Over the last decade many have observed the ways our trinitarianism is indebted to modern theology, but that debt is only the beginning. The rise of kenotic Christology has left no little scar either. I will be ambitious in my systematic then, retrieving the legacy of Chalcedon to be sure but for the purpose of unveiling the ways Chalcedon may provide answers to questions modern theologians did not think orthodox Christology could answer.

I am not alone in such an endeavor. Thomas Joseph White’s book, The Incarnate Lord, has been instructive. Likewise, Dominic Legge’s The Trinitarian Christology of Thomas Aquinas has been illuminating. And, of course, I am returning to the Reformed Scholastic John Owen because he has a way of propelling Christology along until it features prominently in our future hope, the beatific vision itself (see his Meditations and Discourses on the Glory of Christ). Also, I do intend to give attention to the historical development of Christology. Yes, that history is complex but my aim in this systematic is to make the most perplex doctrines lucid for master’s students. The only other option is to ignore such a history or treat it in the most superficial sense, which leaves students of theology in the dark, vulnerable to modernist deviations. To accomplish such a task in Christology, Aloys Grillmeier’s Christ in Christian Tradition will be a companion.

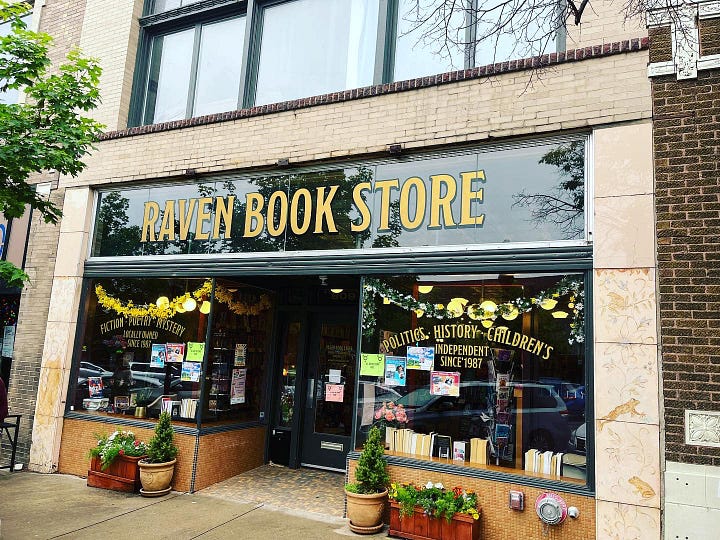

I almost forgot: while I was at KU I took time to explore local bookstores. Some people travel around the country to visit baseball stadiums, but for me it’s bookstores. I came across an old but pristine copy of Mere Christianity—yes, I am one of those people who buys more than one copy of a book. On my walk back to my apartment I read the first chapter once again. Have you ever noticed how C.S. Lewis begins his contemporary classic with natural theology? His argument is common sense, as he puts it, but in the aftermath of modernity and postmodernity we can take nothing for granted. I do think C.S. Lewis’s apologetic will be a great influence on my systematic and I fully intend to return to his other books on miracles and the problem of pain. Truly, Lewis was a medieval mind in a modern world, persuaded the former’s enchanted cosmos was disappearing before his eyes. On that theme, I have been fascinated by his The Discarded Image. His comments on Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy exhibit Lewis’s affection for classical theism—his use of divine simplicity to build a foundation on which human happiness can stand is so absent from treatments of the good life today. My students read Consolation in Theology 2 and I may need to require Lewis’s short commentary from now on.

Speaking of my classes, I now have my schedule for 2023-2024. I plan to use my students to test run chapters of my systematic (don’t tell them). Here are my classes:

Fall

Theology 1 (masters)

Advanced Systematic Theology (PhD)

Christology and Soteriology (PhD)

Spring

Theology 2 (masters)

Philosophical Theology (PhD)

I am pleased to report that I was promoted to full professor this past semester and I am grateful to the leadership of MBTS. After this coming 2023-24 academic year I will enjoy a sabbatical during the 2024-25 academic year and devote myself entirely to the systematic.

In other news, the very first Credo Colloquy has been released! Timothy Gatewood sat down with me and Carl Trueman, and we spent a good hour answering questions and clearing up misconceptions about the Reformation and catholicity, the Scholastics and the Reformed tradition, and the difference between being biblical and being a biblicist. The colloquy oscillated on my about-to-release book, The Reformation as Renewal: Retrieving the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church (Trueman wrote the Foreword) with Zondervan Academic. However, I think those in attendance were interested most of all with Timothy’s hair and Trueman’s Union Jack socks.

As I think through how my systematic will serve the average master’s student in seminary I have become increasingly concerned with the disconnect between classical education (K-12) and Christian colleges and seminaries. Classical education is on the rise, praise God. I substituted recently in my daughter’s classical Christian school and what a delight to see them reading Augustine’s Confessions, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, as well as Plato, Homer, and Milton. But as reflected on my time a question occurred to me: Will these students have the opportunity to carry forward their classical education in college…let alone seminary? Who will show them that their reading of Augustine’s Confessions in humanities has innumerable implications for their development of a philosophy or their orthodoxy in theology? Do they understand that *classical* literature and *classical* theology is a marriage only modernism dares to sunder?

You can find colleges with classical programs, but they are rare, at least those that are Protestant. And classical education disappears entirely by the time a student reaches seminary. With one, maybe two exceptions, I know of no seminary so intentional to formally devote itself to classical theology. Purely from an education standpoint, what a missed opportunity: an entire constituency of classical students are left untapped. The pipeline from classical education K-12 to college to seminary has been plugged for some time. We need plumbers. How bizarre: we open students to the world of Augustine, Dante, and Boethius in their humanities courses, only to send them off to seminaries where they read nothing published prior to the twentieth century. More to the point, we’ve failed to connect the dots between classical literature and classical theology. And then we wonder why students are ignorant of orthodoxy at best or flirting with heterodoxy at worst. I am trying to change this in my classroom, but we really do need seminaries to start honors programs or houses or entire degrees that help students understand why their classical education reaches its fulfillment rather than its extermination in seminary. My systematic is an attempt to be the change, but it will take an entire generation of professors and administrators to make it happen. I hope you will join me to that end.

And to that end, I’d love to see you this November at the inaugural lecture for The Center for Classical Theology in San Antonio, TX (the evening before ETS). Carl Trueman will give the lecture, followed by dialogue with other theologians, and not a few Crossway giveaways. Spots are limited and filling up, so register and reserve your ticket.

I’m Matthew Barrett. Until next time, do explore Credo Magazine, meet other theologians on the Credo Podcast, and participate in the Center for Classical Theology. You can follow me on twitter: @mattmbarrett