Richard Muller, John Webster, and John of Damascus

with reflections on my time with James Dolezal

Last week I announced something spectacular: Baker Academic approached me and asked me to write a Systematic Theology. So why not let you eavesdrop on my research and writing process? Since I am approaching this project out of a spirit of faith seeking understanding, I’ve called this platform Anselm House. Sometimes I will post lengthy musings like I did last time, but sometimes I will post sporadic reports on how my research is progressing, giving you a window into my reading habits which can be eclectic. I’ve always enjoyed Snakes & Ladders, a newsletter by Alan Jacobs which does something similar except in his wild world of literature. (And by the way, can I just say how much I envy his subtitle: more lighting of candles, less cursing the darkness. Jacobs is still one of the best conversation partners I’ve had on the Credo podcast—his wisdom on why the past is the antidote to our anxiety is medicine to the modern soul.)

Warning: like Jacobs, I do enjoy art. Call it sacramental if you desire, call it Platonic if you dare, but all the goodness, truth, and beauty around us is meant to cast our vision heavenward. With permission from classical realism, I will sprinkle my random updates with color from time to time so that we move from shadow to reality. And, since you are eavesdropping, I will occasionally (perhaps more than I should) wander into personal updates and other writing projects, especially as they intersect with my Systematic Theology.

June is a blessed month for my family because swimming at the pool, reading fiction, and feasting with friends are only a few of the sacred ways we spend our hot summers. Yet it’s also an opportunity for me to read.

As I consider the method I will utilize in my Systematic Theology, I have returned to Richard Muller’s Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics like an old friend, beginning with his Prolegomena to Theology. The timing could not be better. Last week I spoke at the Building Tomorrow’s Church conference with James Dolezal, which allowed the two of us to sneak away from the conference and enjoy Arizona’s finest foods in 115-degree heat. Our conversations were peppered with constant laughter—James is hilarious as it turns out and so is Richard Barcellos. (I am just realizing now that James’ shirt says “legendary.”) We also had the opportunity to reflect together on the Reformed Scholastics and their critical appropriation of a Thomistic metaphysic.

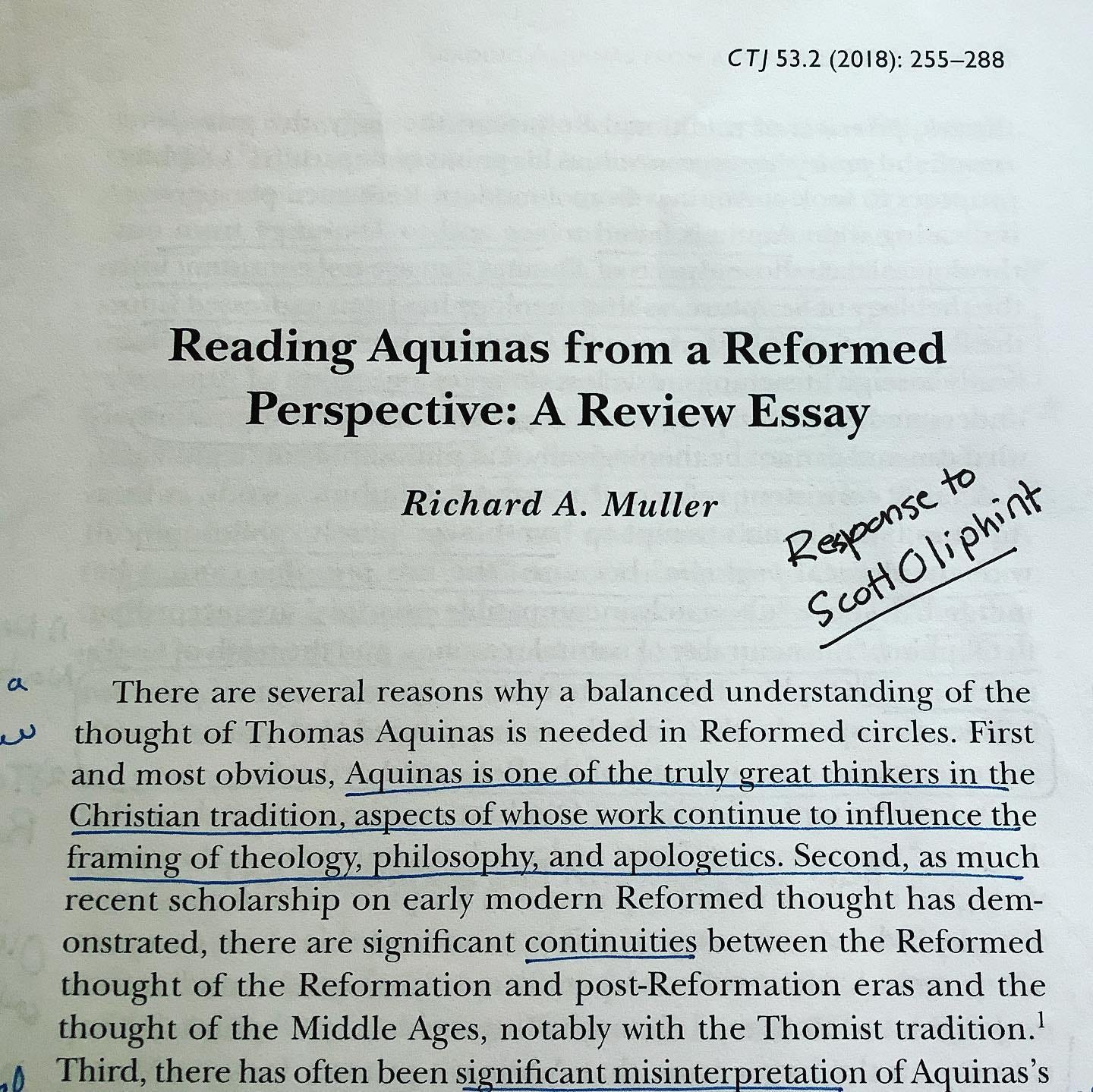

We discussed Richard Muller’s recent critique of Scott Oliphint’s book on Aquinas as well. Muller is a historian, but by the end of his article (read all thirty-eight pages in CJT) he turns theologian and issues a much-needed rebuke in my estimation. It’s an absolute must read, and I plan to make it required reading for my PhD students moving forward. Muller confronts Oliphint’s extreme distortion of Aquinas, revealing why such skewed prejudice against Aquinas betrays the Reformed confessions. Muller goes so far to use the word “sectarianism.”

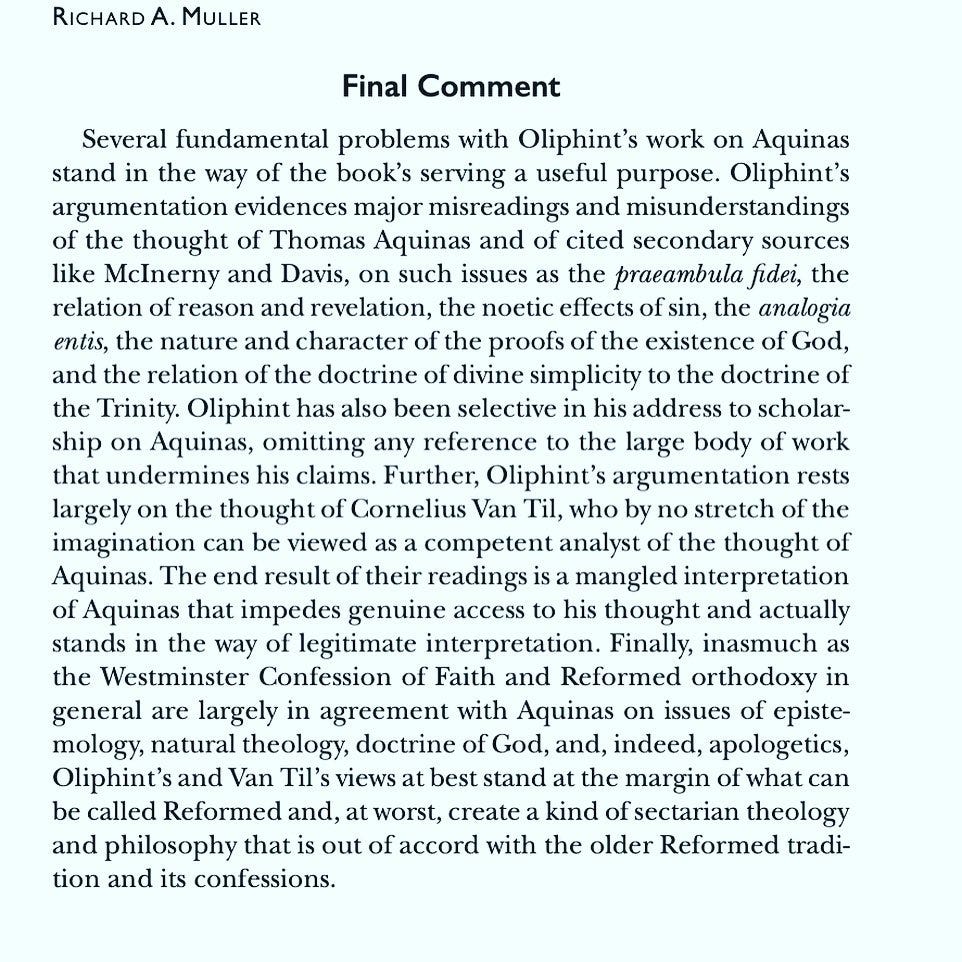

Read Muller’s final comments pictured, but here’s a takeaway line:

“Inasmuch as the Westminster Confession of Faith and Reformed orthodoxy in general are largely in agreement with Aquinas on issues of epistemology, natural theology, doctrine of God, and, indeed, apologetics, Oliphint's and Van Til's views at best stand at the margin of what can be called Reformed and, at worst, create a kind of sectarian theology and philosophy that is out of accord with the older Reformed tradition and its confessions.”

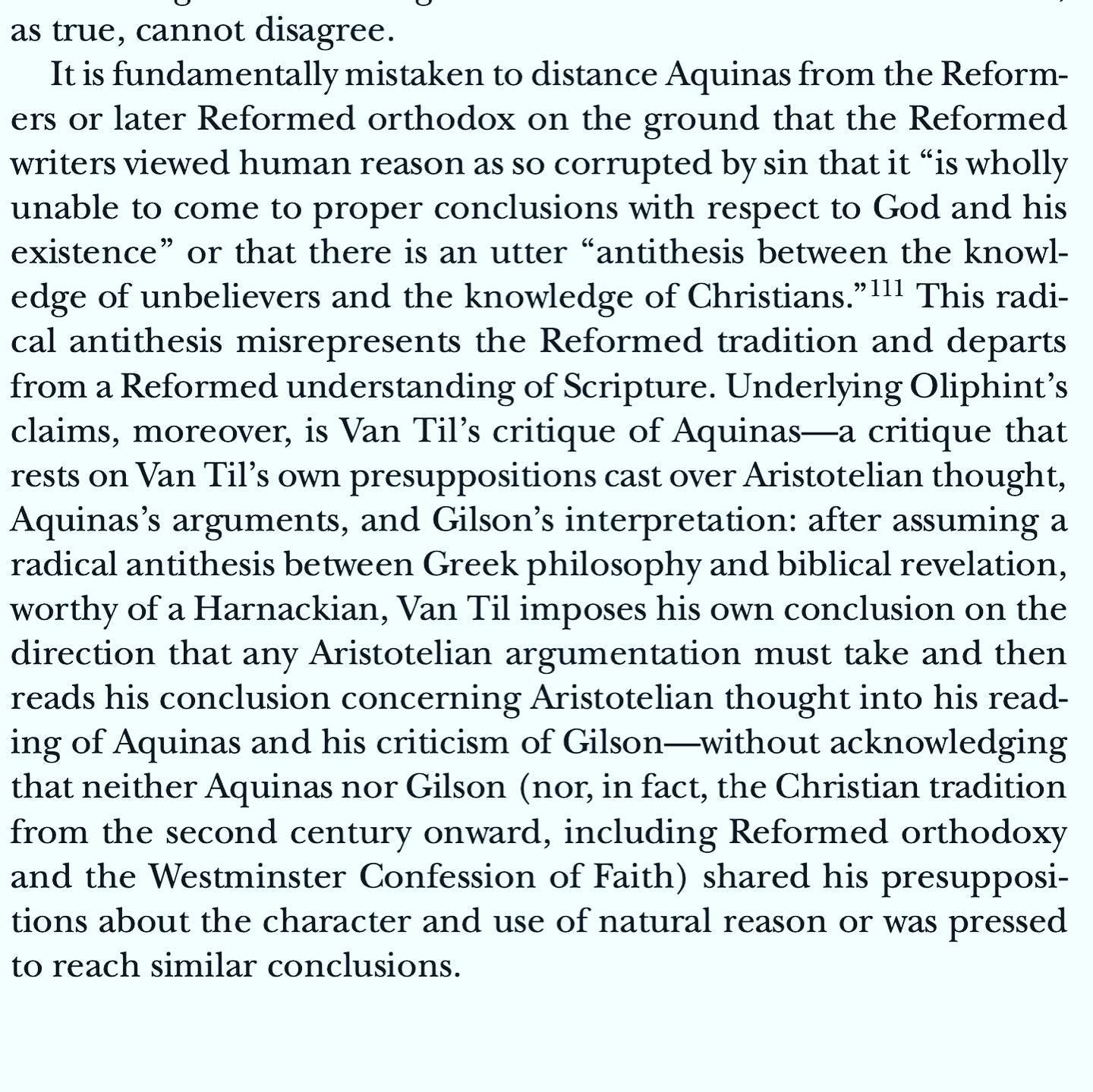

If you thought that warning, by today’s leading Reformed historian, was sobering, I am also including a picture of the page earlier on the Reformation. Muller warns against a radical antithesis that is more like Harnackian Liberalism than Reformed orthodoxy.

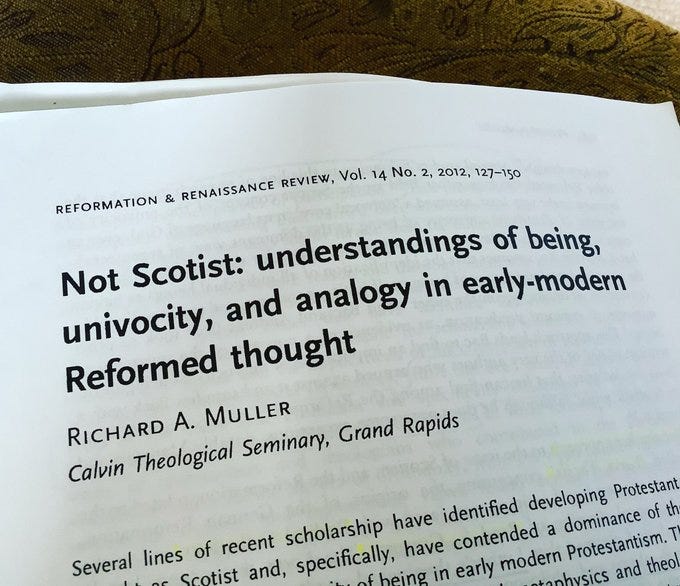

While we’re talking about Muller, I must mention one of his older articles: “Not Scotist: Understandings of being, univocity, and analogy in early-modern Reformed thought.” As usual, Muller delivers. He demonstrates that most of the Reformed Orthodox did not follow the metaphysic of late medieval scholastics like Duns Scotus (being as univocal) but instead followed the metaphysic of high medieval scholastics like Aquinas (being as analogical). The Reformed Orthodox Muller treats are innumerable (Zanchi is a good test case though). Understanding how the Reformed Orthodox critically appropriated a Thomistic metaphysic is key, keeping us from that common accusation (Radical Orthodoxy, Brad Gregory, some Roman Catholics, etc.) of discontinuity which says that the Reformed betrayed a participation metaphysic.

If you are hungry for more, I’m finishing the edits on my 2023 book with Zondervan called, The Reformation as Renewal. The subtitle gives the book away: Retrieving the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church. In Muller’s wake, I have written a fresh history of the Reformation to help us avoid sweeping generalizations of discontinuity, encouraging us to listen to the reformers who claimed—over against Rome’s charge of innovation—that they were more “catholic” than Rome, to use the language of the Creed.

Since I mentioned Dolezal, I should say that you can now watch the videos from the Building Tomorrow’s Church conference. I recommend starting at the beginning with Dolezal’s message on God’s incomprehensibility. I delivered two messages, one on eternal general and the other on inseparable operations and appropriations (with much application to salvation and the Christian life).

Last Sunday was Trinity Sunday. The Gospel Coalition asked me to reflect on why Hebrews uses the language of “radiance” to describe the Son, which gave me the opportunity to quote that famous phrase from the Nicene Creed: light from light.

My article is very short, so if you are eager to explore eternal generation more, I send you to John Webster’s book God Without Measure. In my Systematic Theology I plan to use this quote by Webster, “God’s glory is God himself in the perfect majesty and beauty of his being. The glory is resplendent. Because God himself is light, he pours forth light.”

As for the week ahead, St Vladimir’s Press just released their translation of On the Orthodox Faith by John of Damascus. Damascus proved invaluable to me when I wrote my book Simply Trinity. I am in good company since Damascus proved invaluable to Thomas Aquinas in his Summa Theologiae as well. My plan is to read Damascus again, but this time with a view of the forest, asking myself how he constructed The Fount of Knowledge as a whole. I hope to tell you what I’ve discovered soon enough and how Damascus might influence my project.

Next time I must talk about Jason Baxter’s new book on the medieval mind of C. S. Lewis, which will likely lead me into one of the most important themes of my systematic: participation. A proper understanding of participation is indispensable to a proper utilization of classical theology. And yes, we Protestants do in fact have a doctrine of participation, despite what you hear.

Until then, I leave you two memories, one recent, the other ancient:

Two of my favorite sculptures and paintings, both of which sit only a few miles from my house at the Nelson Atkins Museum (who has a most delicious brunch right outside their reconstructed model of a medieval monastery). Thomas Aquinas from 15th Cent Spain and Last Judgment by Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Feels like an eternity ago, but five years ago I delivered a message at Christ Church North Finchley in North London as they celebrated their history. If I ever had the opportunity to build a church in Kansas City, it might look like this. Transcendence in worship.