This summer I made great progress on my Systematic Theology. I returned to one of my most treasured subjects in theology: the attributes of God. It’s been a while since I wrote None Greater, so I was curious to open this door again, knowing from experience there was far more on the other side than I could possible convey back in 2019. So, allow me to share just one snapshot of my research over these simmering summer months.

Towards the end of my survey of the divine perfections I briefly distinguish between different shades of divine justice, many of which are apparent in the Psalms as well as the prophets (David in Psalms 5 and 11 has been especially pertinent, but so has Habakkuk 1). I’ve noticed that when God’s justice is in the dock, Protestant Scholastic dogmatics follow the patristic and medieval instincts of classical theology. For example, they are quite adamant that divine justice can be distributive but not commutative. Why? Commutative justice, says Francis Turretin, is “based upon an equality of what is given and received and through which authority may be transferred, neither of which can be said of God.” Turretin’s definition reflects the same insight found in Thomas Aquinas’s definition: commutative justice “consists in mutual giving and receiving, for instance in transactions such as buying” explains Thomas.

Does commutative justice sound a lot like theistic mutualism? It does, which is why both theologians are quick to show commutative justice the door. To do so, Turretin quotes the exact same passage Thomas quotes: Romans 11:35, where Paul says, “Of who has given a gift to him that he might be repaid [recompensed]?” Commutative justice, in other words, would subject God to a “give-and-take” transaction, which could only put God in man’s debt. Check Petrus van Mastricht too. Same strategy. The point is, Protestant Scholastics are quite careful, and seriously precise, to follow the logic of classical theism.

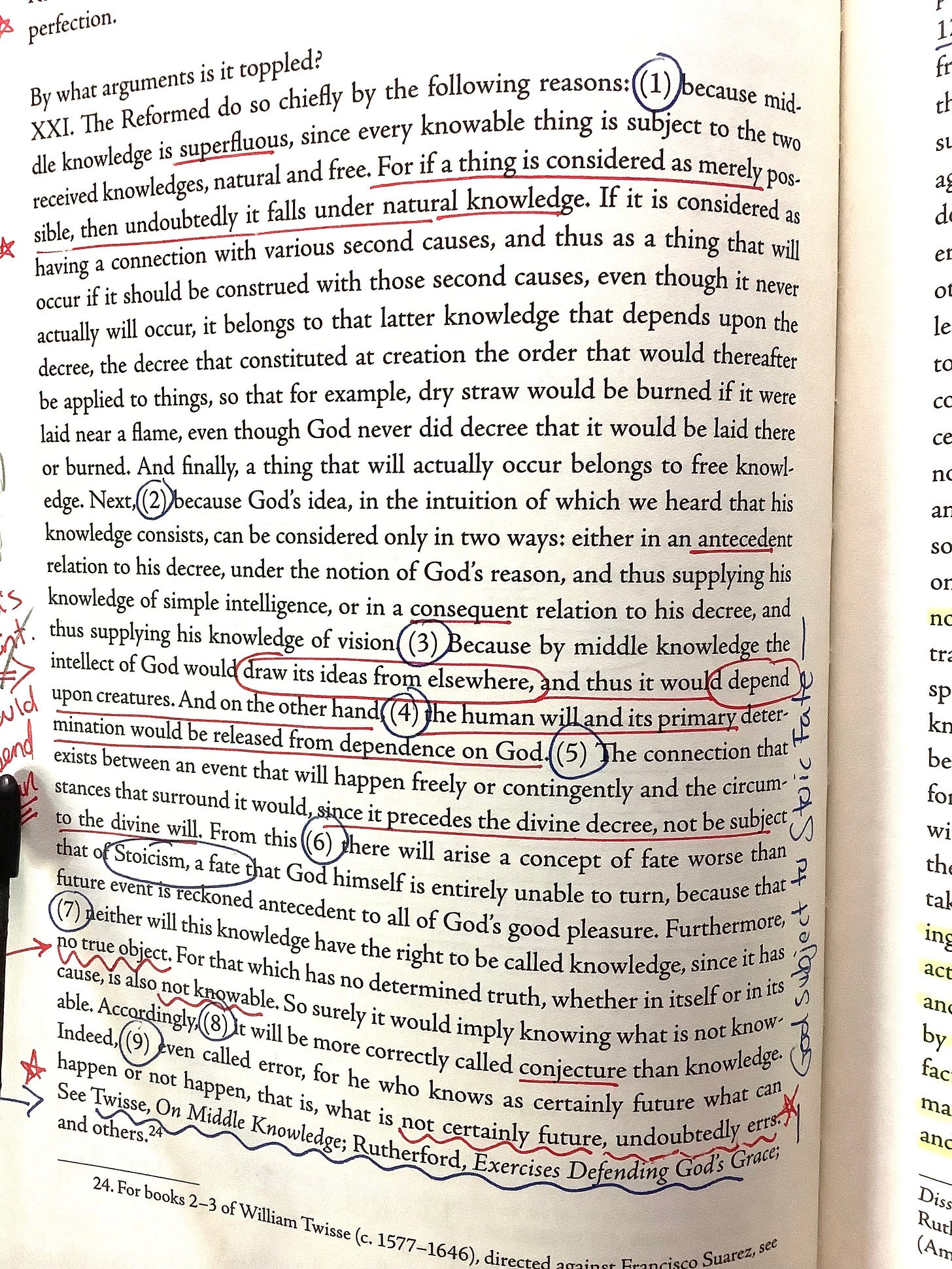

But here is something fascinating (and I hope, if you’re a Protestant, this next point will make you proud of your heritage): Reformed Scholastics then apply these same classical instincts to their reformed understanding of the divine decree. Personally, I’d go so far to call this a contribution. For example, when Mastricht takes on the challenge of middle knowledge in his day (no time here, but if you’ve not heard of middle knowledge before, then do a little research on Luis de Molina), he exercises those same classical muscles. His critique reveals his dire concern that we resist any temptation to condition God, making him dependent in some way upon man for his knowledge (and choices). He gives 9 reasons why. I won’t quote all of them, but here’s a snapshot if you want to read them in detail.

In one sense what the Reformed are up to is quite original: they are transferring classical instincts into the domain of reformed theology. But in another sense, there is nothing original: we’ll never know what a conversation between Thomas and Mastricht over tea (or coffee?) would have been like, but I can imagine a scenario in which they both would have expressed their shared frustrations over Molinism. True, that hypothetical conversation would be lined by different motives: Thomas would have been concerned with the direction Molina was leading Roman Catholics (“My future Dominicans, don’t take this Jesuit bait”) while Mastricht was concerned with Molinism drawing away his Reformed colleagues, even tampering with the good and necessary consequences of their confessions. But who knows, Thomas might have thanked Mastricht in the end since the latter’s instincts are shared instincts, ones others in the Great Tradition might have resonated with as well if they had lived to see the challenges of Mastricht’s day. None of this minimizes differences between Thomas and Mastricht on a variety of loci, nor the nuances in their own presentations of theology proper. But it does remind us that our Protestant heritage retrieved catholic instincts, instincts perpetuating and even refined by someone like Thomas. And the Protestant Scholastics were imaginative enough to ask how those instincts might help them answer modern innovations at the intersection of theology proper and soteriology.

In my systematic, I’m not discussing all this background (though I do allude to it), which is the point of this newsletter. But I hope you can appreciate these subtle vibes of catholicity when you encounter them. I’ll be sharing some of these this Fall as I speak with students and faculty at Benedictine College about The Reformation as Renewal. I plan to report back on my time there.

What else has been going on this summer?

First, some incredible news. For a long time, I have dreamed of launching a Credo conference. Well, it’s finally happening! May 1-2, 2025. Washington D.C. The theme for the first conference? The Trinity. After all, it is the big anniversary of Nicaea in our lifetime. Who will speak? Gavin Ortlund, Fred Sanders, Michael Reeves, Kevin DeYoung, Michael Horton, and myself. But here’s the best part: not only will the speakers walk you through the Nicene Creed, but each of them will lead an Anselm House. In this breakout session you will have the opportunity to join one of these main speakers in a small setting and dialogue with them over a classical text. Each speaker has picked a favorite classical text of theirs (Athanasius, Cyril, Augustine, etc.) that they want to discuss with you. I don’t think you’ll find this type of Socratic dialogue with main speakers at any other conference. Register here and pick your Anselm House before it fills up. One other unique quality: each day the whole conference will say the Nicene Creed together. I would love to meet you in D.C. and link arms around orthodoxy. Will you come join me?

Second, I have edited a book with IVP Academic called, On Classical Trinitarianism. It is what it sounds like. 40 theologians, all writing to recover the Trinity of classical theology for the sake of renewal today. You have the chance to read everyone from Thomas Joseph White to Andrew Louth to Stephen Holmes to Swain & Allen to Carl Trueman. I pray that this book will correct course, amused as the last century has been with revisionist approaches to orthodoxy. I also pray that the diversity of authors will remind us that doctrines like the Trinity are a matter of orthodoxy, and the church universal can unite around them. The book releases October 1st but word on the street has it that it’s showing up in people’s mailboxes already.

Third, the Center for Classical Theology is coming soon! We meet this November in San Diego (the night before ETS) and Michael Horton will deliver a lecture titled, “If Reformed, then catholic: Revisiting sola scriptura.” And (!) G.K. Beale and Michael Allen will join him afterwards for a roundtable discussion. Crossway will be giving away books on the topic as well. Seats are running out so register soon.

I can’t fail to mention either that we are offering a Scholastic Award. It’s a short paper in a scholastic style but the reward for winning is big: the works of Charnock and Owen, plus publication of your paper in a journal. Details here. The deadline is only a month away so submit soon.

In other news, the new issue of Credo Magazine is out: The Revival of Classical Education. I am convinced that if we don’t start our kids off with classical education K-12 then we really can’t expect them to share its values, outlook on the world, and accompanying theology in college let alone seminary. Included in this issue are some all-star articles by educators, some new, some seasoned.

Also, I sat down with biblical scholar Robert Yarbrough to discuss why we love the Bible so much and why we read it with the Great Tradition. Yarbrough has some sobering words about the collateral damage of methodological atheism and need for creeds (especially among Baptists) in hermeneutics. Watch this brand-new Credo Colloquy.