Contemplating the Father with Gregory of Nazianzus

Carefully parsing "unoriginate" and "eternal"

I’ve decided I need a breather from writing the chapters in my Systematic Theology on creation and anthropology. They are thrilling to write as the contrast between a classical approach to creation and a modern one makes for quite a story. Nevertheless, I need to let them marinate for a bit. I write in such a way that I let chapters sit for some time so that I can come back and evaluate them with fresh eyes.

So, I’ve returned to the doctrine of the Trinity in the meantime, immersing myself in the trinitarian texts of the fourth century, which is like meeting up with old friends. In the process I’ve been reminded how important theological precision can be, sometimes the determining factor between orthodoxy and heresy.

For example, I was contemplating the Father, specifically John’s Gospel and what it means for the Father to be without origin (the principle who alone is without principle), when I came across this line by Gregory of Nazianzus: “‘Being unoriginate’ necessarily implies ‘being eternal,’ but ‘being eternal’ does not entail ‘being unoriginated,’ so long as the Father is referred to as origin.” Here’s what I said in my systematic, commenting on Gregory’s point:

Gregory concludes that the Son and the Spirit are from the Father, but they are “not after him.” Even in our human experience with light we understand that something can have an origin but be of the same nature. Consider the sun, says Gregory, from which light proceeds. The light is from the sun, but the light is not inferior to the sun, its source. Or as Gregory says, the sun may be the source of light but “the Sun is not prior to its light.”

Obviously, we should not push Gregory’s illustration (which I also mention in my book, Simply Trinity) to the breaking point, something he cautions against as well. But his warning is to be taken with great seriousness. For if we do not understand the exact relationship between “unoriginate” and “eternal,” we might assume (as some subordinationists did in the fourth century) that the Son and Spirit cannot be eternal since they are not without origin like the Father. In that scenario, only the Father would be eternal since he alone is unoriginate, which would result in the subordination of the Son and the Spirit to the Father. Being “from” the Father would then entail that they are “after” the Father, making the Father “prior” to each of them. Gregory is pushing us to consider how we can affirm that the Father is unoriginate but without projecting hierarchy into the Godhead.

The Nicene creed models Gregory’s point quite well. The Son, it says, is “Light from Light.” On the one hand, the phrase assumes a distinction between Father and Son, one in which that preposition “from” identifies the Father as the Son’s eternal relation of origin and yet does not sacrifice the Father as unoriginate himself. On the other hand, that same phrase “Light from Light” captures the consubstantiality of the Son. True, the Son is not unoriginate like the Father, but that does not preclude him from being eternal. As the rest of the creed reads, this is the Son who is eternally begotten from the Father. And if he is eternally begotten from the Father’s divine nature, in which the Father eternally communicates all the perfection of his divine nature to his Son, then the Son cannot be inferior to the Father. Light from Light is a subordinationist defeater in the creed.

Why does this matter? It matters because we need to speak of the Father as that person in the Trinity that is unoriginate, as Gregory says. However, we must learn to do so in a way that does not lead us into the swamp of subordinationism, as if the Father has priority over otherwise inferior persons (the Son and Spirit). That misstep is a costly one, ultimately eliminating the Son and Spirit from our worship.

If you want to read more on the subject, explore On God and Christ (look at 3.29.3). On that note, I am excited to share with you some news: with the help of Credo and a slew of theologians, we’ve launched TheNiceneCreed.org. There you will find 12 short Videos, each by a different theologian, walking you through the creed. Plus, included are additional pages with other videos answering tough questions. I really hope this resource will assist pastors and churchgoers alike, giving them an onramp to the Trinity.

In other news, I can hardly believe it but the Credo Conference is almost here, just over a month away. I’m talking to the other speakers, and I think the breakout sessions will be special. They are almost full, so if you haven’t registered, now’s the time. By the way, several publishers (Crossway, B&H, Christian Focus) will giveaway books to every attendee. So plan on entering the conference with arms ready to embrace some books on theology!

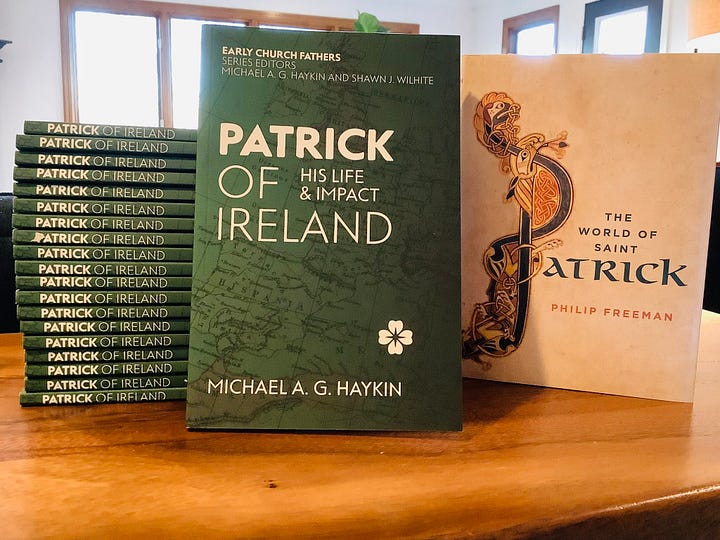

In other news, Anselm House met again and on St. Patrick’s Day. We read Patrick’s Confession. One thing we talked a lot about: in the church we often push back the Trinity, as if it’s irrelevant until someone is a very mature Christian. But the Gospels do just the opposite, making the Trinity the centerpiece in evangelism, baptism, and discipleship. Saint Patrick is exemplary: “Since I believe in the Trinity, I must make known the gift of God.” A big thanks to Christian Focus who sent along Michael Haykin’s Patrick of Ireland, so that these theologians could leave with a great from the Great Tradition.

Last, to all you dedicated podcast listeners, you will be pleased to hear that both Michael Horton’s lecture from the Center for Classical Theology, as well as the Q&A with Horton, G.K. Beale, and Craig Carter are now up on the Credo podcast. Enjoy.